This is partly my take on whatever takes my fancy. After 20 years' experience in various Aboriginal domains, I don't believe public policy has the imagination or the flexibility to deal with Indigenous peoples. Politics preoccupies me. My blog is also about writing - and therefore thinking - in Plain English. Call it an obsession, if you like, but somebody's gotta care. And, finally, it's about living in that weird and wonderful place, the Northern Territory

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Stinking fish

But there's something particularly putrescent about the current crusade against Islam.

One of our national newspapers devoted many column inches over the weekend to a solemn explanation of how terrorism may be justified in the teachings of this fine human creed.

Islam, therefore, stands condemned as explicitly condoning violence.

Right.

Given that Islam postdates Christianity and Judaism both, but shares some of the same scriptures, let's unpack that one a bit.

The teachings of Christianity have been used to justify:

the ruthless extirpation of old religions by the burning of 'witches' and the torture of infidels and pagans;

the Crusades

the protection of orthodoxy by the painful execution of heretics and the damning of 'free' thought - Galileo and company;

pogroms against the Jews in Poland, Russia and - yes - the excrescences of Nazi Germany at Buchenwald, Mauthausen, Oswiecim and the countless prisons of the regime;

the spread of imperialism and capitalism, with the cross following the sword and the cash register to bring 'civilisation' to the world; and

institutionalised racism in contemporary America, Australia and other countries.

The New Testament isn't quite all airy-fairy sweetness and light, but it pales beside the blood asnd thunder of the Old.

The moral of the story is that people in glass houses shouldn't be throwing stones or demonising.

In Australia, this kind of demonisation has taken on a new twist.

The discovery of child sexual abuse in Aboriginal 'communities' (places set up for the administrative convenience of government and religion) has opened the way for the more rabid of our conservative politicians and their lickspittle kommentariat to condemn Aboriginal cultures as condoning it.

This has opened the way for a power grab and a return to paternalism; stricter controls on accountability and restrictions on funding.

You set up zoos which have no relation to the way Aboriginal people want to live and then blame them for behaving worse than animals

It's one of the smellier episodes in our contemporary politicial life, consistent with our conservatives accusing illegal immigrants of throwing their children overboard from refugee boats to prop up an unconscionably inhumane immigration policy.

Yes, there's something very smelly around our political scene.

And it's not just rotting fish.

The very cheapest populism rules and it ain't OK, particualrly when they 'find' a basis in religion to support it.

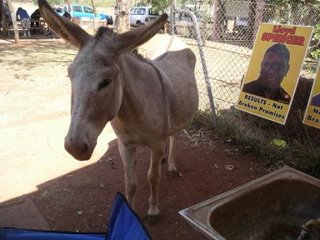

Donkey votes

For the benefit of overseas visitors to this blog, Australia has a preferential voting system at all elections and it's compulsory.

You have to cast a vote for every candidate in order of preference by nunbering every square on your ballot paper.

Every political party hands out How to Vote cards with their preferred order of candidates.

It's supposed to be fairer than first past the post. But it means someone who doesn't get the most first preference votes can still squeeze through if they get enough preferences from other candidates.

Some ballot papers show the person voting cast their votes in numerical order from top to bottom. That's called a donkey vote.

But I never thought I'd see it so literally!

On the campaign trail

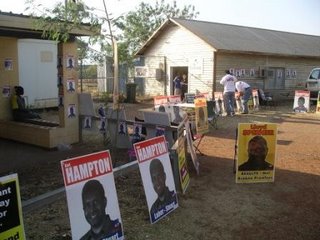

Last week I was out bush helping with mobile polling in the southern part of the Victoria River District.

As voting is compulsory in Australia, everyone has to be seen to be given the chance to vote.

So the Australian Electoral Commission sends out teams to collect votes in every remote community in the Territory.

And each political party sends out workers to hand out how to vote cards and soothe theircandidates

Where it's really remote, they come in by helicopter.

We went on a roadshow - 1900 km in three days.

Here's some pics of what it was like.

From top to bottom:

Two Labor MPs, Barbara McCarthy, Member for Arnhem (left) and Marion Scrymgour. Member for Arafura and Minister for Environment and Heritage, among other things, with a very tall punter who was keen to have his pic taken with them. Basketball (or in Kriol basgitbol) anyone?.

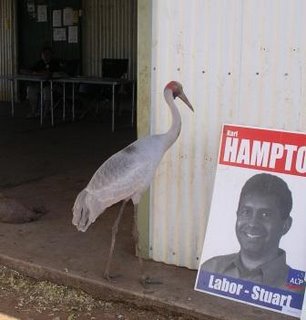

Brolgas can't vote. But that didn't deter this tame brolga (or Native Compantion, one of Australia's two true cranes) from hanging round the polling booth at Pigeon Hole.

The polling booth at Kalkaringi.

And at Daguragu, voting bush style.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Rewriting history, and then some

I've just come back from the twin communities of Daguragu and Kalkaringi, about 750km south-west of Darwin, the home of the Gurindji people, whose country extends an hour's drive to the east and a little further west.

More about why I was there in another post.

It's beautiful rolling savannah, emphasised by a few low hills and rocky ridges and outcrops.

One of these ridges - Wave Hill - gave its name to the cattle station whose stockmen were Gurindji.

And their struggle, which gave birth to the land rights movement in Australia, is what put it into the history books.

The station was selected in the late 1880s by old man Buchanan and up until the 1950s ran on largely unpaid Aboriginal labour.

From about the time of the First World War it was owned by the British Lord Vestey, a hugely wealthy absentee landlord.

Anthropologists Ronald and Catherine Berndt were hired by Vesteys in the late 1940s to investigate how Vestey's couild recruit more Aboriginal people into the industry.

That investigation turned into a damning report on industrial and living conditions on the Vestey stations that was shelved for more than 40 years.

It was finally published as 'End of an Era' in the early 90s.

The report, in sparse prose, related how Vesteys cruelly exploited Aboriginal workers, who were little more than slaves, working for rations - soup bones, offal, salt beef flour, sugar, tea and tobacco - and clothes.

Boys as young as 11 started in the industry and worked til they dropped.

Their health was poor and injuries went untreated.

While it is true the stations took care of dependants, they all had to do some work about the place for their short rations - children, the aged and the infirm

Many old men gimp around with broken hips, a common injury when you're on horseback around cattle.

From about the 1950s, there was a minimum wage and for many of the older men it was the first time they'd seen real money.

For others, who had worked for the Army during World War 2, it was back to the good old days.

In the 1960s the labour movement - mainly the wharfies and the North Australian Workers Union - began to agitate seriously for equal pay for Aboriginal stockmen.

The pastoralists argued vehemently against it, pointing out thaty Aboriginal stockmen weren't worth as much as whites.

And yet the industry had relied on their labour for more than half a century.

The Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission eventually handed down its decision in 1966, proposing a gradual intriduction of equal wages over the following three years.

But the Wave Hill stockment had already had enough.

Led by Vincent Lingiari (that's his grave at the top of this post), they walked off Wave Hill station - men, women and children - and four days later camped at Wattie Creek.

It wasn't an arbitrary choice of camp.

Apart from having good water year-round, Wattie Creek is also Lawi - dreaming place for the Rainbow Serpent.

The significance of that escaped me until I visited the place last week, but it's now clear to me that a people who were believed to be fringe dwellers with no culture had all along nurtured it away from prying eyes.

Where else to go when you're turning your back on oppression?

The story of the strike is told in Frank Hardy's Unlucky Australians, a book that's as much about Frank as about the Gurindji.

Some of the srtikers went south and told of their conditions at union meetings.

Lupgna Giari, a Mudpura man, was questioned by journalists.

Surely stockmen got more than salt beef and flour? Oh yes, sometimes they bin put more salt on the beef.

But somewhere along the line, it emerged that striking for equal pay was only the tip of the iceberg, to use a geographically inappropriate metaphor.

What the Gurindji really wanted was their own land back.

The company and the government of the day tried everything to get them to go back to work.

Govenrment money eventually paid for housing at Kalkaringi, the site of the present-day community and then site then of the old Welfare rations depot.

But they sat it out.

Eventually Gough Whitlam came and poured the famous handful of sand into Vincent Lingiari's hand as he handed over the lease to the land.

They built another community at Daguragu, close to Lawi.

Early this month the Gurindji and their friends - among them Frank Hardy's son and granddaughter - joyfully celebrated the 40th anniversary of the walk-off.

There was a couple of sour notes, however.

One was the death of an old man from Daguragu.

And the other was the emergence of a revisionist history of the cattle days that asserted that the station owners were deeply saddened by the Wave Hill walk-off and all the other walk-offs that happened across Northern Australia.

They hadn't been in the interests of Aboriginal people and had forced the pastoralists into modernising their practices and employing fewer people.

That's a bit like blaming African Americans for getting equal rights and ending tghe colour bar.

But one of the the few surviving strikers had the last word.

Old and frail Hoppy Mick Rangiari - another one bearing the broken hip as a legacy of his days on the catttle - got up from his wheelchair and told the people at the celebrations; 'That Bestey been treat we like dogs'.

I'm with Hoppy Mick.

I trust the history that is in people's bones.

Friday, September 22, 2006

Reds under the bed

But it's for our convenience, not theirs.

To try and accommodate crazy whitefella ideas and get the funding they need to run the towns, build the houses and so on, they try to make the councils work in a way that allows for some expression of Aboriginal ways of doing things.

In some places, it's making sure that every clan is represented on the council.

That way the benefits are more likely to be shared equally - new houses, sewerage, council positions.

It doesn't quite work to the satisfaction of the beancounters, but it generally passes muster.

Except for our boofhead Federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs, that is.

Mal the Mouth was heard to rant at a conference of policemen recently that clan-based community councils were nothing more than 'communist collectives'.

I kid you not.

Mal pretends to be unaware that the only member of the Marx family to have any impact on Aboriginal people was Groucho.

And he should know that the most widely-read book in Aboriginal domains is the Bible.

Emphatically not Das Kapital.

So why the rant?

One of my earlier blogs mentioned dogwhistle politics and this is a classic example: the subtext says these communist collectives are un-Australian, so the normal rules don't apply.

The Government is within its rights to subject them to scrutiny and cut off their funding if there's a sniff of suspect practices.

Which of course the government will find.

It's always easier in politics to demonise people.

It worked for George Bush.

But I don't think even he would return to the Cold War era to find a justification for reactionary and repressive policies.

Sunday, September 10, 2006

Maningrida (or Manayingkarrira)

Two giants of European contemporary art flank an emerging giant of the art world in posters on a wall in Basel, Switzerland. John Mawurndjul is from Maningrida, a community of 2000-odd at the mouth of a river in Central Arnhem Land. Mawurndjul was on the cover of Time magazine earlier this year and is one of a half-dozen Aboriginal artists from various parts of Australia who have contributed work to the interior design of the Musee de Quai Branly in Paris. He painted a supporting column and part of the ceiling.

The 'rarrk' in the poster refers to the cross-hatching and other devices in bark and body paintings that bury the real meaning of the story that's been painted. An Aboriginal painting in these domains is not simply a work of art; it's also a statement of identity, inheritance and right - right of ownership of land or to a ceremonial story that confers responsibilities for land, resources or family. That true story is closed to people who are not entitled to know it, but they may be told an abridged and simplified version - the 'outside' story - while the real one - the 'inside' story' - remains safe and secure in plain sight.

I'm flying out there tomorrow on a work visit, looking at how the community is managing on the Community Development Employment Project. It's a program through which people voluntarily work for their legal entitlement to unemployment benefits. The program is under attack from the Federal Government, which wants Aboriginal people everywhere to have 'access to the free market' and embrace capitalism. Both of these are difficult concepts for people like Mawurndjul, whose apparently considerable income from painting supports an extended family.

More on this later, when I get back.

Tuesday, September 05, 2006

Violence

Dopy Dave had jumped on unrest about juvenile crime and organised a 'community forum' with the sole intention of gaining a bit of political capital.

He'd invited the Federal Minister for Justice along and this Minister made the astounding suggestion that we go back to hitting kids at school to help solve the problem.

I couldn't believe it and I said so: was he seriously advocating common assault as an element of our educational philosophy?

The interviewer, playing devil's advocate, asked me if I'd been subjected to corporal punishment at school, and whether it made me behave.

I went to a boarding school on England which, pace the late David Sandison, I will call St Onan's.

I was caned on the backside and on the hand with wooden and bamboo canes, beaten with gym slippers (what we used to call 'Trainers', dear) and was the target of blackboard dusters or viciously thrown pieces of chalk.

Old Thos, the woodwork teacher, would hurl a lump of wood at innocently daydreaming kids and accompany the 'thunk' of it hitting your head with the declamation: 'behold thy fairy godmother', delivered in a South Yorkshire accent.

I was also imprisoned (school detentions on weekends), I was bullied (made to do repetitive and degrading drills) stood over and sexually assaulted. And that was just by teachers.

The conservative response is to say '...and it never did me any harm'.

Bullshit.

Violence begets violence and assaults of this nature are psychologically damaging even if all they engender is a deep-rooted belief that violence is an acceptable solution.

I didn't behave. I was humiliated and resentful of my personal space being invaded so intimately and with such ease.

People who don't think things through particularly well always come back to a violence-based discipline approach (behavior management, they call it these days) as THE answer.

They also tend to blame schools for kids running riot, when it is essentially a social problem.

And if society can't or won't deal with it, there's little point demanding that schools accept the entire responsibility and empowering them to assault into the bargain.

I'm raising this here because I've been thinking about the way Aboriginal people are mystified by our culture's ability to perpetrate an atrocity like the Stolen Generations, a psychic as well as physical wound which reverberates down through succeeding generations.

'How could you do it to children?' they ask.

'After all the stuff you talk about families, how could you take children away from their mothers?'

The asking, I think, carries an implicit assumption that there may be something, some answer, that will explain everything.

There is no logic to it.

But you can gain some insights into how it happened by looking at the way many among us are prepared to treat children from our own culture - particularly the children of the marginalised, who are themselves marginalised educationally and who are likely to carry on what have become family traditions of being economically marginalised.

I was a smart working class boy and my teachers were generally of a middle class educated elite.

Much of what I went through may well be described dispassionately as rites of passage.

But they did it because they could get away with it - and they did.

And, clearly, there are still people in power who think it's OK to advocate violence against children as a panacea for social ills.